In doing some research lately, I had translated an article on Puncetto from an old Italian monthly magazine: Vita Femminile Italiana [Italian Women's Life] from 1907. It occurred to me that perhaps you might like to read it as it is not something you would normally come across. Any errors in translation are my own.

|

| Clorinda Favro's Diploma from the Genoa Italian Exposition of Women's Work, 1903. |

Valle Vogna and Puncetto

by Modesta dell’Oro Hermil. Vita Femminile Italiana, 1907.

It seems like a fairytale. Once upon a time in a valley far, far away… way up high up in the mountains, there were poor women, young and old, gathered in small huts buried in the snow. Their fathers, husbands, brothers far away in a foreign land to earn their bread. The women, alone in their miserable, difficult life. Finished the few brief tasks of their primitive family life, here they are in the light of the white snow reflected through small black narrow windows and in the evening in the light of the flame, here are the poor fingers that in summer are hardened by the harsh work in the fields, now in the break from the misery, become the nimble fingers of fairies. From those poor fingers blossoms lace, real Alpine flowers, real snowdrops of work, and the fine needle, shiny and patient, works and etches like an engraver.

And that strong brilliant work then adorns the shoulders of the workers and the lace supports the shoulder basket. Dear Italy, my beautiful homeland, where the light of art, a flower of beauty, emanates and is revealed even among the rocks, even among the poverty, even in the solitude, in the hardship.

And one day a lady, no, I mean the good fairy, passed by in the months in which the work bustles in the fields. Her expert and practised eye rested on those laces, true carved ivory. Her heart was touched by so much courageous poverty and rude work and the gaze of the artist was attracted to that form of feminine art.

And so it was that Mrs. Lynch, on a pilgrimage from Ireland, discovered the Valle Vogna and Puncetto.

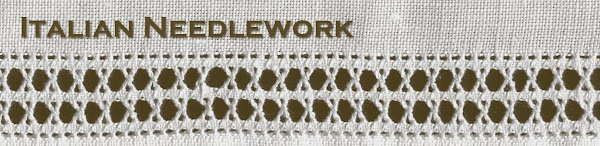

Puncetto, the alpine stitch, the strong lace of the peasant women. The fundamental stitch is a double buttonhole stitch, that is: a second loop is made in the first and the two combined form a knot so that the lace can be cut without unraveling.

Puncetto is the word of the dialect of some valleys to the south of Monte Rosa for this lace that forms part of the local peasant costume. The seams of their blouses made of linen woven at home, are connected by the lines of incrustations of this lace.

Generally, women in the region are small, delicate, but they work harshly; they are the log splitters, the water bearers, cheese makers, shepherdesses, field workers; it is therefore necessary that every part of their dress can withstand the roughest jobs. “It is made for eternity” say they, and in fact it must be strong! In the summer those frail shoulders carry the trunks of the strangers who spend a few warm weeks at the only little hostelry of the valley.

A visitor to whom those weights seemed cruel said, “Send me a mule for my trunk. It is full of books, I do not want one of these girls to carry it.” He was told: “There is not one of them who would not regret the half lira that you will give for taking this trunk down to Riva, and a mule would cost more.” And they do it with gratitude.

Money is so scarce! And they take down and bring up those terrible weights on those rough roads, almost like staircases in parts. There are only women and children to struggle with the rocky soil. The picturesque slopes are rough to cultivate, almost only pendent edges, onto which frequently a layer of earth must first be brought and then carefully fenced, sheltered, supported, otherwise it would be washed away by rain and lost.

For a few weeks in the summer many women can earn some money by carrying huge weights on their shoulders, not only trunks, but also beams to the sawmill and staves to the Cooper, but how many times these small earnings are spent in anticipation!

Where and when was Puncetto first made?

The peasants who wear it, in Valsesia, Valle Vogna and the nearby valleys answer: “it is very old; it was old at the time of our grandmothers.”

The alpine women of Parrè in the Bergamo Alps produce a lace very similar to Puncetto and they associate it to the time of the plagues, saying that even then it was already an old authentic lace. At the time of the plague the women of Parrè vowed that neither they, nor their descendants would ever change their ancient costume, nor would they ever follow the dictates of fashion if only the plague were stayed. Outside the Sesia Valley, in other parts of the Alps, the same quality of lace is called “ivory stitch”, “saracen stitch”, “greek stitch” and “alpine stitch”. Saracen stitch could be the name given to anything in the days when the terrible pirates reigned terror down on the inhabitants. Towers, castles, hills, mountain passes, still carry the names of Saracens even when history shows no correlation between them and anything moorish.

The name “greek lace” may be supposed to be due to that many of the closest, tightest patterns of Puncetto have a distinct resemblance to the ancient handwoven linen used in the early pieces of Cutwork.

The oldest of all forms of lace was the Drawn-thread Work, the second, Cutwork and both forms flourished in Byzantium in the days of the Roman Empire. Puncetto, under its various names is only found in the Alps. A scholar of the history of lace expressed the theory that the Alpine stitch is the third age in the family of lace. We must not forget that Puncetto, although it is an authentic and beautiful lace is rather a kind of idealized macramé and not the soft spider webs of Honiton, Valenciennes, Point de Bruxelles, etc.

These rich rigid substantial laces have their own special use, they are especially suitable for household linen and everywhere where an edging of fine passementerie or gimp would go nicely. Puncetto takes a long time to execute and can never therefore be done cheaply.

A former schoolteacher, during twenty-seven long years, taught the girls of Valle Vogna to use their needle as true artists during the long harsh winters. She sensed the opportunity, the benefits that the foundation of an industry of lace would offer to her pupils. No one better than she could understand the misery, the gloom of the long months of winter, when, ill-fed, ill-heated many of those girls did not even have the relief of work, but spent the long painful hours waiting for May.

The snow begins to fall generally in mid-October to melt, then fall again. At Michaelmas the cattle descend from the high Alps. Some go to fairs, others spend the winter at lower levels, others are installed in one of the divisions on the ground floor of the châlet, which becomes the living room. A solitary weaver said, “I stay here in the winter, my cow is such a nice companion!"

The husbands, the fathers, sons, brothers, boyfriends come back, if they want and if they can, from France with a small hoard to spend a few weeks in the brown châlets where they were born.

But a long and fierce winter has already passed before Christmas brings the men home and another still long and terrible one must pass before the return of spring. It is already late in the year before the field work can be restarted in the higher regions.

Poor, dear old teacher who kept that little flame of art and work alive, lit in the snow, in the silence, in the abandonment! And now from Ireland comes the intelligent and generous aid, and now that little flame has become the great fire of good industry, of well being that warms hearts and the small châlets. She had the satisfaction of seeing the lace industry launched and thriving before going to her final rest in death.

The story of the small Industry is a story of struggle. When Mrs. Lynch admired the lace, she thought it may offer a means to lift the extreme poverty of many of those women. She believed that when one can such produce a rare and artistic thing, one must find a market for the work. She gave, and conducted the introductions to give orders: collars, cuffs, borders for blouses, lace for lingerie. They were successful. Requests came for pillowcases, tea-table cloths, bedclothes. Gradually they found new uses for the strong lace; altar linens, work bags, etc. An American lady conceived a summer outfit with inserts of seven different lengths of Puncetto from Valle Vogna.

From poor Ireland came encouragement and invaluable assistance.

The Daily News of June 1897 announced: “Some of the curious and beautiful point lace of the Valle Vogna, (resembling Greek lace), is being mounted on Irish linen by the Irish Industries Association for Queen Margherita. It is to be offered to Her Majesty by some of her lace making peasant subjects. The Countess Bective has designed the royal crown for the different pieces. They can be seen at the Irish Depôt, Motcomb St., Belgrave Square.”

In the Queen newspaper of November 5, 1898: “The Val-Vognian Peasant’s Work. Last winter an Italian gentleman took to Rome, for presentation to Queen Margherita, a tea-table cloth, d’oyleys, and a cushion, trimmed with the handsome lace edgings and insertions made by the Val-Vognian peasants. Her Majesty has just sent, by the hand of the same Piedmontese gentleman 300 lire to be distributed among the workers. They are delighted at this Royal bounty. They never dreamt of reward beyond the honour of the Queen’s acceptance of their work. Now this gift will make a great difference in the lives of three or four poor châlets.”

So it began, laborious and ascending. Queen Margherita, whose private collection of lace is of great beauty and value, continued to buy. It was good - she is so surrounded by all the smiles and tears, as in all high art and the humble work of her people, and also Puncetto made from strong and patiently knotted threads in huts buried in the snow, now rigid and serene in the Royal Palace.

In the six or seven months of the winter reclusion they worked on a bedspread ordered by Her Majesty. It is copied from a pattern from about 400 years ago, the work of an Arab, probably a prisoner. The signature can be seen in the margin of the original piece. A pair of curtains of the same pattern were made at the request of the Italian Minister of Agriculture and Commerce and they go to the St. Louis Exposition. As a door curtain, curtains, etc., these embroideries are Arab-Val-Vognian - admirably suitable and highly artistic. Their true name is: Cutwork. One pair of these curtains gave work to five women over two years.

The lace done now in Valle Vogna is finer, more even, better designed than the Puncetto of eleven years ago. The industrious workers were given samples of the laces and embroideries of Greece, Bosnia, Hungary and they have copied almost every sort of complicated works of art. They make beautiful towels with knotted fringes that the Arabs introduced to the Mediterranean coasts. They collected photographs of the sculptures of Byzantine Ravenna beautifully suited for Puncetto patterns.

The dear alpine women like to give special names to their laces. The Mice Ladder for a mass of tiny thin bars. The Lattices of Alpe Motta - for a lace made of criss-crossing lines - Daisies - Rosettes - Lucia’s Pearls - Carolina’s Roses - Trefoils - I Give You Good Morrow - Forget-Me-Not, etc. So much unconscious poetry! In 1899, four women were occupied all day for each day of the week. In the winter of 1900-01 eighteen lacemakers were in constant employment and also the weavers found a market for their linen.

And they are so glad for each new order, their letters are so full of gratitude! “I must tell you something Signora; when I became too weak for field-labour and our only cow was dead, I said to myself: now my mother and I will perish from hunger. And then came the lace orders. It is as if the hope of work gave me courage and health. We are happy ever since.”

Lately Valle Vogna had the honour of a request to supply samples of Puncetto, Drawn-thread work and Cutwork from the Royal Museum of Brussels.

Collectors add samples of this special lace to their collections. In the winter Emily Holness’s store Valle Vogna Industry in San Remo at No. 8 Via Vittorio Emanuele sells pieces of Puncetto and in the summer in Ormea from the same Miss Holness. They can be found still from the Ghersi ladies at Courmayeur, Fräulein Huber’s shop in St. Moritz, from Frau Kniel in Davos-Platz.

In London Puncetto suitable for dress purposes is at Sheba’s in No. 15 Sloan Street, S.W. and the bigger pieces at Walcot’s, Moulton Street, W.

For any purchase or order or clarification or samples it is best to contact Signora Clorinda Favro, Casa Verso, Valle Vogna, Province of Novara. She is the Chief worker in the Industry. She won a gold medal at the Genoa Exhibition and a diploma from the Ministry of Agriculture, Industries and Commerce.

Land of misery and now land of cheerfulness.

The whole history of the Valley Vogna is contained in these words.

Poor dear old lady who’s death Mrs. Lynch saw as a blessing. She was believed the first director; she had never seen her do anything for nothing; the nothing - material that implies great spiritual wealth, continually. Then she understood that tenacious, patient, ardent goodness. And in the last hour she saw again the harsh work of summer, the long frozen winters, lonely, dark, like painful vegetating, not a life but a non-death; saw again the poor hands slowly working the Puncetto of home!

Then she saw the large group of happy and industrious workers, saw the flow of beautiful designs, beautiful antique laces, the multiplication of the work in the better-lit, better-heated huts, saw the poor Puncetto leave for distant countries, go to the Queen, go to museums. She saw a new light of prize-winning work, of intelligence, of emulation and closed her eyes - blessed in that vision and wished that the good old lady might be told that for her "a land of misery is now a land of cheerfulness.”

Dear little old lady of Valle Vogna!

How beautiful the word “cheerfulness" is. She didn’t say wealth or progress - cheerfulness - joy, the bloom of honest, appreciated work; the fruit of the labour, not only in money, but in moral development, in the well-being of the soul.

Kind ladies, make a place among the gauzy laces and soft silks, make a place for the strong Puncetto of Valle Vogna. When you go out in the summer sun, ascend to the mountains in fresh outfits of good linen, make a place for Alpine stitch.

The soft laces of the living rooms in our artificial light; at the top, in the open air, is the Puncetto worked by hands that have reaped, tilled: the Puncetto worked in winter huts, that blossomed at the foot of the mountains like the edelweiss pure and strong.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Many thanks to Bianca Rosa and Ivana!